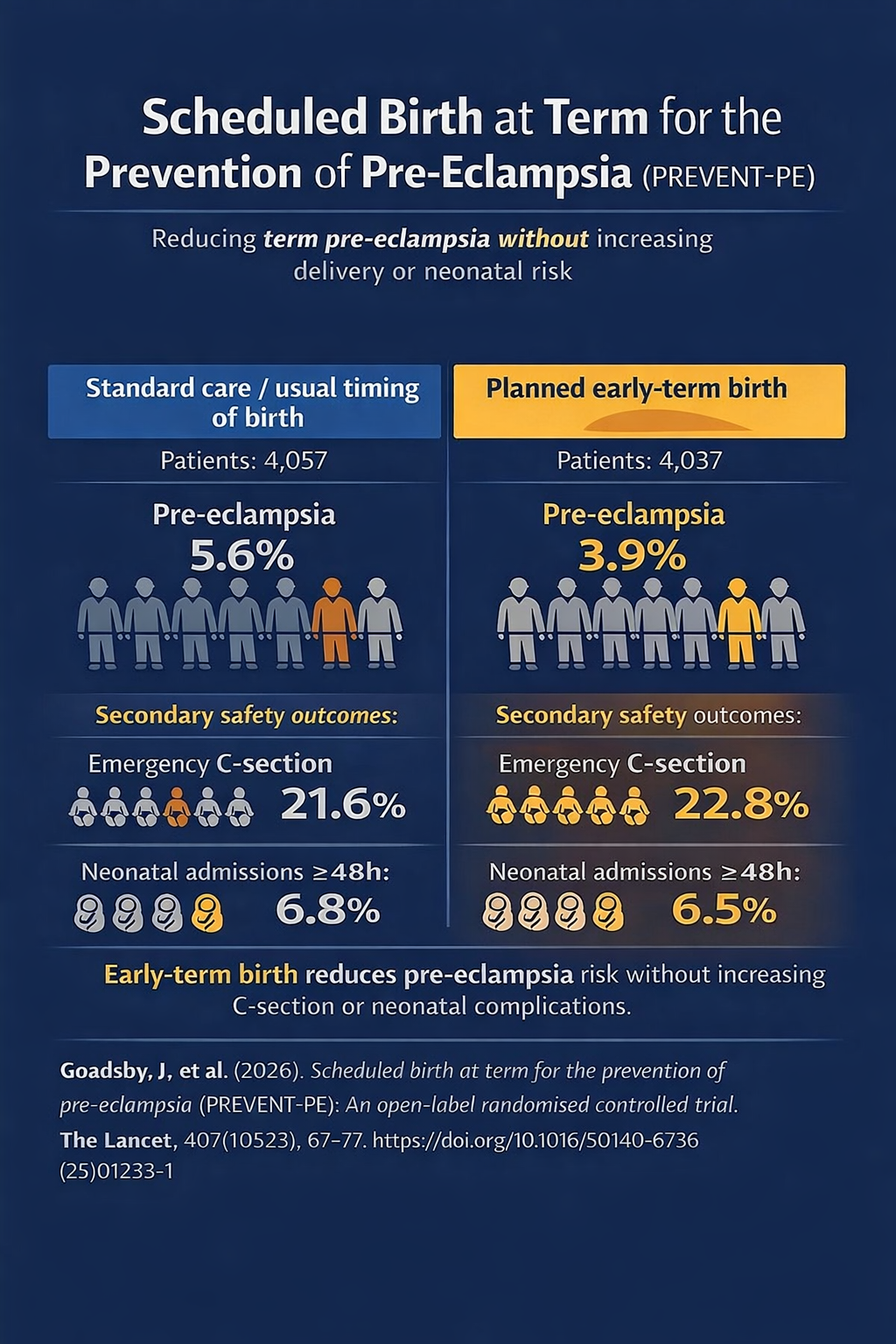

Risk-stratified screening at 36 weeks, followed by planned early-term birth in high-risk women, significantly reduces the incidence of term pre-eclampsia without increasing maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes. This provides evidence for a pragmatic, late-pregnancy prevention strategy.

In Brief | Women's Health, Maternal Wellbeing

Maternal Wellbeing: Risk-Stratified Early-Term Birth Reduces Term Pre-Eclampsia

14 January 2026

Screening for pre-eclampsia at 36 weeks and offering planned early-term birth in high-risk women significantly reduces term pre-eclampsia without increasing maternal or neonatal harm.

Quick Facts – PREVENT-PE Trial

- 8,094 women ≥36 weeks’ gestation, diverse obstetric population.

- Risk-stratified screening at 36 weeks + planned early-term birth reduced term pre-eclampsia: 3.9% vs 5.6%.

- No increase in emergency C-sections or prolonged neonatal admissions.

- Strategy offers a pragmatic late-pregnancy prevention approach, relevant to high-risk settings like South Africa.

Top

Study Objective

The PREVENT-PE trial sought to determine whether screening for pre-eclampsia risk at 36 weeks’ gestation and offering risk-stratified, planned early-term birth reduces the incidence of pre-eclampsia, without increasing maternal or neonatal harm.

Study Summary

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy remain a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide, with pre-eclampsia posing a particularly high burden in low- and middle-income countries. Despite extensive research, there is currently no reliable intervention to prevent term pre-eclampsia in women identified as high risk late in pregnancy.

The PREVENT-PE trial sought to address this gap by evaluating whether risk-stratified screening at 36 weeks’ gestation, followed by planned early-term birth for high-risk women, could reduce the incidence of pre-eclampsia without causing maternal or neonatal harm.

PREVENT-PE was designed as an open-label, adaptive, randomised controlled trial, and was conducted at two UK maternity hospitals. Eligible participants were women aged ≥16 years with a singleton pregnancy, no established pre-eclampsia, and the ability to provide consent. A total of 8,094 women were enrolled (4,037 intervention; 4,057 control), representing a demographically diverse cohort with 25.9% identifying as non-White.

The median maternal age was in the early 30s, and the median body mass index was approximately 29 kg/m², reflecting contemporary obstetric populations, including those seen in South Africa’s urban public sector.

Women in the intervention group underwent risk assessment at 36 weeks using the Fetal Medicine Foundation (FMF) competing-risks model, with planned early-term birth offered to those with a predicted risk of ≥1 in 50.

Control participants received usual care, consisting of expectant management to term. The primary outcome was pre-eclampsia at birth, defined according to the 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) criteria.

Study Fndings

The trial demonstrated that pre-eclampsia occurred in 3.9% of women in the intervention group compared with 5.6% in the control group (adjusted relative risk 0.70; 95% CI 0.58–0.86).

Importantly, planned early-term birth did not increase rates of emergency caesarean section (22.8% vs 21.6%; RR 1.06) or neonatal unit admissions lasting ≥48 hours (6.5% vs 6.8%; RR 0.96).

Significant reductions were also observed in antenatal pre-eclampsia and its clinical components, including proteinuria, maternal organ dysfunction, and thrombocytopenia.

Risk-stratified screening at 36 weeks, followed by planned early-term birth in high-risk women, significantly reduces the incidence of term pre-eclampsia without increasing maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes. This provides evidence for a pragmatic, late-pregnancy prevention strategy.

Why this is Relevant for South African Practitioners

In South Africa, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy account for approximately 18% of maternal deaths, with pre-eclampsia affecting an estimated 9.6% of pregnancies.1 The burden is compounded by higher rates of severe disease, delayed presentation, and avoidable health system factors. Incidence of pre-eclampsia in Africa has risen by approximately 20% over the past decade, and African women are at intrinsically higher risk due, in part, to population-level genetic factors influencing maternal–foetal immune interactions.2

Within this context, the PREVENT-PE trial is particularly relevant for South African practice. The study demonstrates that a planned, protocol-driven approach to early-term birth can reduce the incidence of pre-eclampsia without increasing maternal operative delivery or short-term neonatal harm. In resource-constrained public health settings—where hypertensive disorders place substantial pressure on emergency obstetric, neonatal, and critical care services—this strategy offers a potential means of reducing severe maternal complications, improving predictability of care, and optimising use of limited healthcare resources, while maintaining safety for both mother and infants.

Original Study

References

2. African women at higher risk of pre-eclampsia – The Conversation, May 6, 2025.

The content in this summary is intended as an overview only and does not replace the original research. Members should review the original study before forming clinical opinions. The Medical Education Network cannot be held liable for inaccuracies or omissions.

Fact-checking Policy:

The Medical Education Network makes every effort to review and fact-check source material. Please use the contact us form to report issues.