Quick Links

Overview | Pharmacokinetics & Drug Metabolism | Opioid Use Clinical Practice | Side Effects | Monitoring | Parental Education | Opioid Addiction | Conclusion | References

Access to adequate pain management remains a global challenge, with the Declaration of Montreal (2010) recognizing it as a fundamental human right. Nonetheless, over 80% of the global population, particularly vulnerable groups such as children, pregnant women, the elderly, and individuals with mental illness or substance dependency, continue to face inadequate pain relief.

While various recommendations advocate for a multimodal approach to managing acute pain—incorporating non-pharmacologic therapies, opioid and non-opioid medications — it is opioid medications that remain central to the management of moderate to severe paediatric perioperative pain.12

Opioids fall into three classes: natural opioids, such as morphine and codeine; semi-synthetic opioids, such as oxycodone; and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl. These opioids differ in potency; for example, fentanyl is up to 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. When combined with other medications, such as sedatives, these drugs can prove fatal.1

In South Africa, the 2021 discontinuation of tilidine (Valeron™) has left practitioners with limited options for managing acute pain. Morphine, tramadol, and oxycodone are now the most commonly used alternatives, though robust data on their safe use in paediatrics remains scarce.13,17

In 2021, guidelines released by the South African Society of Anaesthesia (SASA) reviewed the safe opioid prescribing practices in paediatric and adolescent patients.15

We review the high-level recommendations contained in these guidelines, based on a 2022 review article published in the South African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia (SAJAA), alongside recently updated information from the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) regarding the use of codeine-containing products, and the guidelines recently released from the American Academy of Paediatrics in September 2024.13, 16

This review is not exhaustive but aims to provide an overview of opioid use in paediatric patients. Practitioners should refer to the SASA paediatric guidelines for the safe use of procedural sedation and analgesia for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in children (2021–2026).15

Back to top

Age-related variations in pharmacokinetics and their impact on drug metabolism

The efficacy and side effects of opioid analgesia vary significantly with age due to the highly variable pharmacokinetics of opioids.Absorption varies significantly by age groups and by route of administration.13,17

Neonates

Neonates (0–28 days) experience the greatest absorption variability, as decreased protein binding and an increased volume of distribution result in a higher free fraction of opioids. They have a higher gastric pH, delayed gastric emptying, and reduced bile salt formation, affecting the bioavailability of orally digested drugs. For example, acid-labile drugs like penicillin exhibit increased bioavailability in these infants, while weakly acidic drugs like phenobarbital show decreased bioavailability. Reduced intestinal motility and enzymatic activity in young infants also contribute to slower drug absorption.11

In contrast, transdermal absorption is enhanced in neonates due to a thinner stratum corneum and higher surface area-to-weight ratio, whilst intramuscular injections, often avoided due to pain and risk of tissue damage, demonstrate erratic absorption due to variability in muscle mass, injection depth, and circulatory status. Inhaled drugs, however, are less influenced by physiological factors and more by the delivery method.11

Immature hepatic and renal systems significantly reduce morphine clearance to less than 10% of levels seen in older children. abdominal hypertension, renal insufficiency, acid-base disturbances, and impaired cardiac function frequently experienced in premature infants further reduced the morphine clearance.

Increased blood-brain barrier permeability in neonates heightens their susceptibility to opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI), necessitating a 50–70% dose reduction in neonates (<10 days) compared to standard recommendations.13

Young Infants and older children

By six months of age, opioid clearance and metabolic pathways approach those of older children. For example, both fentanyl and sufentanil clearance increase significantly during infancy; alfentanil clearance, in particular, remains lower in neonates compared to older children. In contrast, remifentanil clearance peaks in neonates. From 2 to 11 years of age, this enhanced clearance and a larger volume of distribution increase the risk of under-dosing.13

From adolescence onward, pharmacokinetics resembles adults, placing these patients at particular risk for both under and over-dosing.

These pharmacokinetic variations emphasize the complexity of dosing across age groups and the need for tailored analgesic strategies.

Back to top

Opioid use in paediatric pain management

Morphine

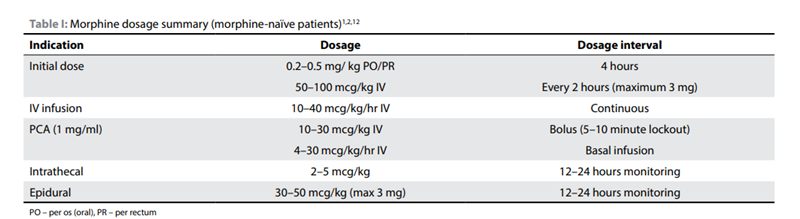

Morphine is the most widely used opioid in children, demonstrating efficacy and safety across all age groups. It has been included on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines since 1977, and there are well-established dosing regimens for its use in paediatric patients.20

Morphine acts primarily as a mu-opioid receptor agonist and is administered via various routes, including intravenous, oral, neuraxial, subcutaneous, and intramuscular. Each administration route poses unique challenges in these young patients.13

Oral morphine, in particular, has low bioavailability. A study conducted in 2019 by Dawes et al., which aimed to characterize the absorption pharmacokinetics of enteral morphine in children and simulate time-concentration profiles based on common oral dose regimens, found that oral morphine had a bioavailability of 0.298, with significant serum concentration variability (5-55 mcg·l-1) at steady state. A single 100 mcg·kg-1 dose achieved peak concentrations of 10 mcg·l-1, while repeated doses resulted in mean steady-state concentrations of 13-18 mcg·l-1, levels were associated with effective analgesia.

This study supports the current recommended regimens of 0.2-05mg/kg followed by 50-100 mcg·kg-1 every 4 hours or 150 mcg·kg-1 every 6 hours to provide effective analgesia.

Conservative dosing is advised for neonates, infants, and children with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), given their higher risk of opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI).13

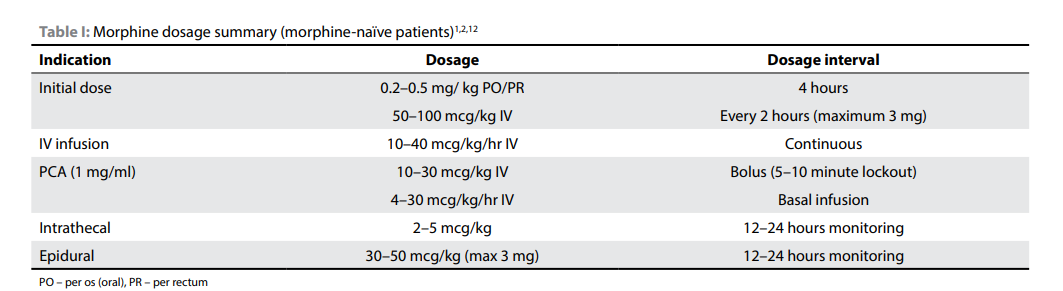

SASA Recommended Dosage

Table 1 contains the recommended dosages for opioid-naïve children. Click to enlarge the image. .3,13

Source: Redelinghuys, C. (n.d.). Paediatric analgesia: Perioperative opioids. South African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 28(5), 45–49.https://www.sajaa.co.za/index.php/sajaa/article/view/2893/3168

Back to top

Codeine Use in Paediatric Populations

Codeine is a prodrug, which is converted by the cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme into morphine and morphine-6-phosphate.

Terminology Decoder

Prodrugs are pharmaceutical compounds with little to no pharmacological activity. When acted on by various enzymes, they metabolise to a pharmacologically active drug. These drugs have much better pharmacokinetic properties such as distribution, metabolism and excretion, and are increasingly used in drug deveopment.10

CYP2D6 is a key gene in pharmacogenomics, encoding a cytochrome P450 enzyme that is responsible for metabolising approximately 20% of commonly prescribed medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, analgesics such as opioids, and anticancer drugs.6

Classified as a weak opioid, codeine’s efficacy and safety are influenced by genetic polymorphisms in CYP2D6, which determine the patient's metaboliser phenotype.4,13,15

Phenotypes include:

These phenotypes and the resultant differing clinical responses led to growing concerns regarding the use of codeine in paediatric and neonatal populations.

In 2013, the FDA recommended that alternatives to codeine be used for post-operative pain in children undergoing tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) issued similar warnings, and the WHO removed codeine from its analgesic ladder in 2012. 4,13

In 2017, the FDA extended its warning to include breastfeeding women, children under 12, and adolescents with obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), or severe lung disease. 4,13

Then, in July 2024, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) issued a statement that codeine-containing medicines pose significant risks of respiratory complications in children under 12, including fatal outcomes. Consequently, SAHPRA mandated that codeine-containing products clearly indicate that codeine is contraindicated in children under 12 years and in children under 18 undergoing surgeries for tonsil or adenoid removal due to OSA. It furthermore issued special warnings and precautions for its use in children with respiratory conditions.16

These restrictions align with EMA and FDA recommendations to mitigate risks associated with codeine use in vulnerable populations.

Back to top

Oxycodone

Oxycodone, a semi-synthetic opioid, is twice as potent as morphine. Only 10% undergoes metabolism by CYP2D6 to oxymorphone and noroxymorphone, both of which have been associated with increased OIVI in ultrarapid metabolisers.2

A recent study which compared the efficacy and safety of oxycodone and tramadol as postoperative analgesics in children aged 3 months to 6 years undergoing elective surgery, found that adequate post-operative analgesia can be achieved with intravenous oxycodone with less side effects than tramadol.7

Patients received a loading dose (1 mg/kg tramadol or 0.1 mg/kg oxycodone) followed by parent-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) with fixed bolus doses (0.5 mg/kg tramadol or 0.05 mg/kg oxycodone).

The study found that both drugs provided similar pain relief, with no significant differences in FLACC scores. Both drugs had the same common side effects. However, oxycodone was associated with less sedation and shorter PICU stays compared to tramadol. The results of these findings indicate that oxycodone may be an effective choice for pain control in these patients.8

SASA Recommended Dosage

The recommended oral dose is 0.05–0.1 mg/kg every four hours. If renal impairment is present, an increased dosing interval is recommended.13

Editors Note

There is limited evidence on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of synthetic opioids in paediatrics, apart from morphine. Fentanyl, sufentanil, and alfentanil exhibit faster clearance in infants and older children compared to neonates, while remifentanil clearance is highest in neonates, with a consistent half-life across age groups.

According to the EHA guidelines, due to immature clearance, synthetic opioid dosages should be reduced in neonates for the first 2-4 weeks and up until 44 weeks post-conceptual age for premature infants. For remifentanil, the effective half-life in neonates is similar to that of older children and adults and thus requires no adjustment. 4

Tapentadol is a centrally acting analgesic with a chemical structure similar to tramadol. It functions as a mu-opioid receptor agonist and a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor.

Only 15% of tapentadol is metabolized via CYP450 enzymes, and its analgesic effect is not dependent on its metabolites.13

This distinct metabolic pathway differentiates tapentadol from other opioids like morphine and tramadol, where active metabolites play a significant role in their analgesic properties.

Tapentadol was first licensed for use in adults in 2011. In 2018, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved it for use in hospitalized children aged 2 to 18 years for the treatment of moderate to severe acute pain, offering an important alternative for paediatric pain management.

A key study conducted in 2019 by Finkel et al. assessed the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of tapentadol oral solution in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years with moderate to severe postoperative pain.

The multi-centre, open-label trial involved 44 participants who received a single 1 mg/kg dose of tapentadol oral solution. Results indicated that the serum concentrations of tapentadol and its metabolite, tapentadol-O-glucuronide, were within the range observed in healthy adults, confirming that children metabolize the drug similarly to adults. Pain intensity scores improved significantly following the administration of the drug. Treatment-emergent adverse events, such as vomiting and nausea, were reported in 45.5% of patients, but no serious adverse events were observed, indicating that tapentadol is generally well tolerated by paediatric patients.5

This trial supports tapentadol oral solution as a promising new option for paediatric pain management, particularly in the postoperative setting. However, further studies are necessary to establish long-term safety and efficacy in children.

SASA Recommended Dosage

The recommended dosage for paediatric patients is 1 mg/kg every six hours, with a maximum dose of 100 mg per administration.13

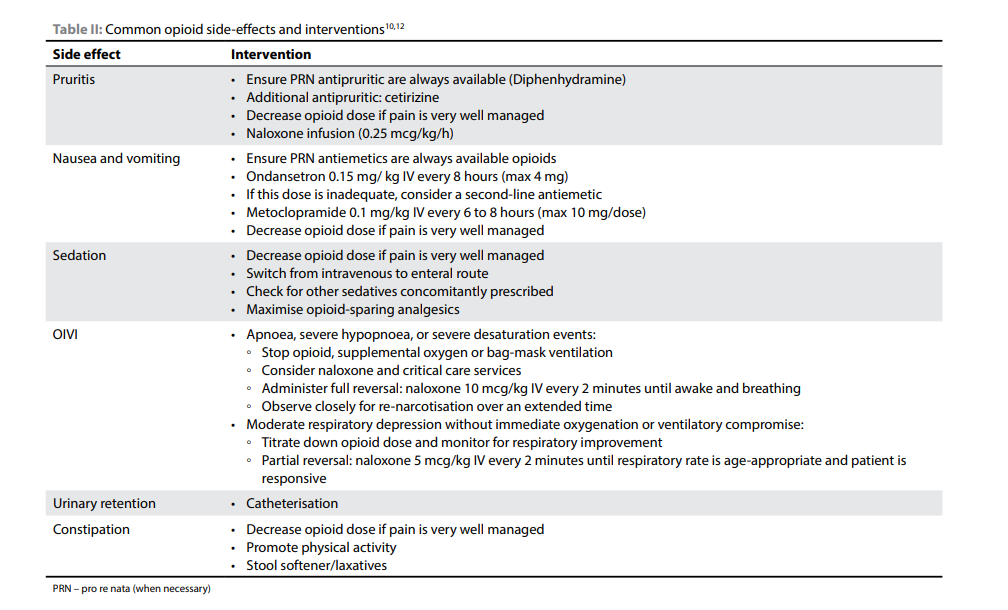

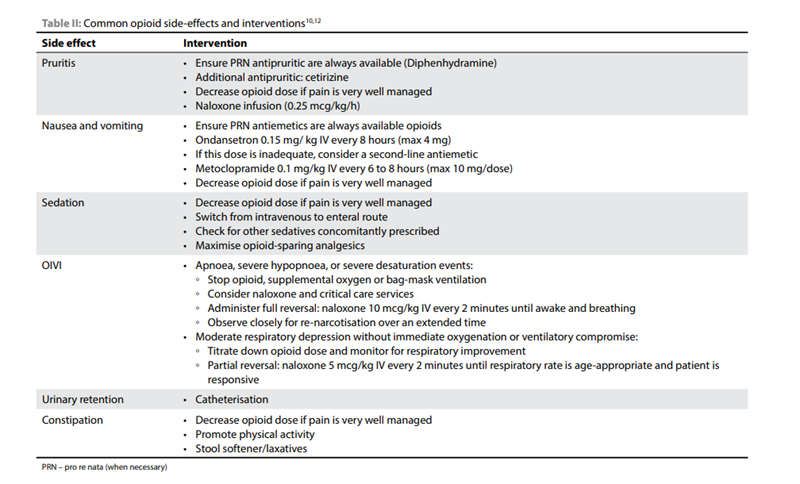

Opioid side-effects and Management

Opioids are generally well tolerated in children, but as with adults, they are associated with some common side effects, including nausea, vomiting, sedation, and pruritus.

These side effects are experienced at a similar frequency in children as in adults. However, children with certain comorbidities, such as obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), severe neurodevelopmental conditions, trisomy 21, and severe epilepsy, are at higher risk for opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI). For these high-risk groups, a reduced opioid dose of 50–75% is recommended to minimize the risk of adverse effects.13

Chest wall rigidity, a rare but concerning effect of opioids, involves a combination of glottis closure and chest wall rigidity, which can be influenced by factors such as the dose, speed of opioid delivery, and the age of the child. This condition is more commonly seen with synthetic opioids and in younger children. Neuromuscular blocking agents and induction agents may help reduce and manage these side-effects.13

Additionally, there is ongoing concern about pain sensitisation as a potential long-term effect of opioid use. Opioids like morphine and fentanyl may have neurodevelopmental effects, although this remains a topic of considerable debate. As such, alternative analgesic strategies should be considered in paediatric patients.

In September 2024, the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) released its first-ever Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents with acute pain. Whilst these guidelines were specifically tailored for outpatient settings, of note was the specific caution against prescribing codeine or tramadol for children under 12 years of age or for adolescents aged 12 to 18 who have conditions such as obesity, obstructive sleep apnoea, or severe lung disease.1

The guidelines indicate that opioids should also not be used for postsurgical pain following tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy in patients under 18 years of age. Additionally, caution is advised when treating acute pain in children who are on sedating medications, as these can exacerbate opioid side effects.

Finally, the guidelines address the risks associated with discontinuing or rapidly tapering opioids in individuals who have been using them long-term to manage chronic pain. Such abrupt changes can cause harm, and clinicians are urged to manage opioid withdrawal in these cases carefully.

Table 2 below highlights the commonly occurring side effects and their interventions. Click to enlarge the image13

Source: Redelinghuys, C. (n.d.). Paediatric analgesia: Perioperative opioids. South African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 28(5), 45–49.https://www.sajaa.co.za/index.php/sajaa/article/view/2893/3168

Monitoring of patients on peri-operative opioid therapy

Paediatric anaesthetists play a key role in perioperative pain management, and accurate pain assessment is vital to guide appropriate care. However, insufficient data exist to support the beneficial effect of routine pain assessments on patient outcomes, and inconsistencies in practices are common.

Nonetheless, routine, validated pain assessments are crucial to avoid under- or overuse of analgesics and to ensure optimal pain relief while minimizing harm. Pain assessments should be multi-dimensional, developmentally appropriate, and use validated instruments, considering the unique circumstances of the child, surgery type, and psychological factors.17

Of particular note, monitoring paediatric patients on opioids is crucial to minimise the risks of opioid-induced ventilatory impairment (OIVI). While serious OIVI is rare, the risk is higher in infants under one month and children with co-morbidities such as neuromuscular disorders, cognitive impairment, or obstructive sleep apnoea.

Back to top

Post-operative Opioid Use and Parental Education

Adequate postoperative pain management in children is essential, yet evidence shows that pain is often poorly managed at home following surgery. Procedures such as tonsillectomy, dental extractions, and circumcisions frequently result in significant postoperative pain after discharge.

The AAP Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend a multimodal approach that combines nonpharmacologic therapies and nonopioid medications, with opioids used only when necessary. Importantly, opioids should not be prescribed as the sole treatment for acute pain in paediatric patients.1

Where opioids are indicated, the guidelines advise using immediate-release formulations at the lowest appropriate dose based on age and weight. In most cases, opioids should be prescribed for no longer than five days unless longer treatment is warranted, such as after trauma or surgery.

Several barriers contribute to inadequate pain control in children, including parental misunderstandings about opioid requirements, dosing errors, concerns about side effects, and children’s refusal to take medications. Parents may underuse opioids due to fear of adverse effects or over-administer them in response to perceived sedation. To address these issues, comprehensive discharge instructions—both verbal and written—should include clear guidance on pain management strategies, the safe use of opioids and nonopioid options, and protocols for medication storage and disposal. Educational resources, such as informational brochures, can further support parents in managing their child’s pain effectively.

Back to top

Note on Opioid Addiction

In 2019, the global prevalence of non-medical opioid use was estimated at 1.2% among adults aged 15–64 years. In 2021, a UN World Drug Report highlighted that Africa, particularly North, Central, and West Africa, played a significant role in global opioid seizures, with the continent accounting for 87% of such confiscations, largely due to tramadol trafficking.

Projections indicate a 40% increase in drug users across Africa by 2030, highlighting the growing concern regarding opioid misuse and trafficking in the region.,13,19

Although data on opioid use in South Africa are limited, the non-medical use of over-the-counter (OTC) prescription opioids, such as codeine and tramadol, is prevalent in several sub-Saharan African countries.

Research suggests that up to 5% of adolescents exposed to opioids for postoperative pain management may face the risk of persistent opioid use. This further exacerbates the challenge of ensuring adequate pain relief, especially for vulnerable groups, where the stigma surrounding opioid use can contribute to inadequate pain management. Given these concerns, clinicians must carefully balance the need for effective pain relief with the potential risks associated with opioid use.1

Effective perioperative analgesia is essential, and opioids may be necessary in some cases, but prescriptions should be limited to the immediate postoperative period. In instances of opioid addiction, non-opioid analgesics should be optimized, though opioids should not be withheld when required for adequate pain management.

Inadequate pain relief, particularly when a child is facing surgery or multiple invasive procedures, can contribute to delayed healing, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other long-term emotional challenges. While opioids are necessary for moderate-to-severe pain, not all acute pain requires their use. Recent studies suggest that conditions traditionally thought to necessitate opioids, such as tonsillectomies and acute fractures, may be managed effectively with acetaminophen and NSAIDs alone, with fewer side effects.

Opioids should, therefore, be reserved for cases where pain remains inadequately controlled with non-opioid treatments, and their use must be carefully balanced with the clinical need for pain relief and the risks associated with their use in this vulnerable population.

6. Health Education England. (n.d.). CYP2D6. Genomics Education Programme. Retrieved 26 November 2024 https://www.genomicseducation.hee.nhs.uk/genotes/knowledge-hub/cyp2d6/

7. Kane M. Oxycodone Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype. 2022 Oct 4 [Updated 2024 Aug 21]. In: Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M, et al., editors. Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584639/

13.Redelinghuys, C. (n.d.). Paediatric analgesia: Perioperative opioids. South African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 28(5), 45–49.https://www.sajaa.co.za/index.php/sajaa/article/view/2893/3168

14.Rosen, D. M., Alcock, M. M., & Palmer, G. M. (2022). Opioids for acute pain management in children. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 50(1–2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057X211065769

17. South African National Department of Health. (n.d.). Paediatric Standard Treatment Guidelines (STGs) and Essential Medicines List (EML): Session 2 [Webinar]. Retrieved from https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/webinar/paediatric-standard-treatment-guidelines-stgs-and-essential-medicines-list-eml-session-2

19. Tlali, M., Scheibe, A., Ruffieux, Y., Cornell, M., Wettstein, A. E., Egger, M., Davies, M. A., Maartens, G., Johnson, L. F., Haas, A. D. (2022). Diagnosis and treatment of opioid-related disorders in a South African private sector medical insurance scheme: A cohort study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 109, 103853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103853

Disclaimer

Every effort has been made to attribute quotes and content correctly. Where possible, all information has been independently verified. The Medical Education Network bears no responsibility for any inaccuracies which may occur from the use of third-party sources. If you have any queries regarding this article contact us

Fact-checking Policy

The Medical Education Network makes every effort to review and fact-check the articles used as source material in our summaries and original material. We have strict guidelines in relation to the publications we use as our source data, favouring peer-reviewed research wherever possible. Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained here accurately reflects the original material. Should you find inaccuracies or out-of-date content or have any additional issues with our articles, please make use of the Contact Us form to notify us.