Clinical Review | Transplant Medicine, Nephrology

Transplant Medicine: Expanding kidney donor pools: 'Africa First' study highlights the promise of controlled donation after circulatory death

18 November 2024

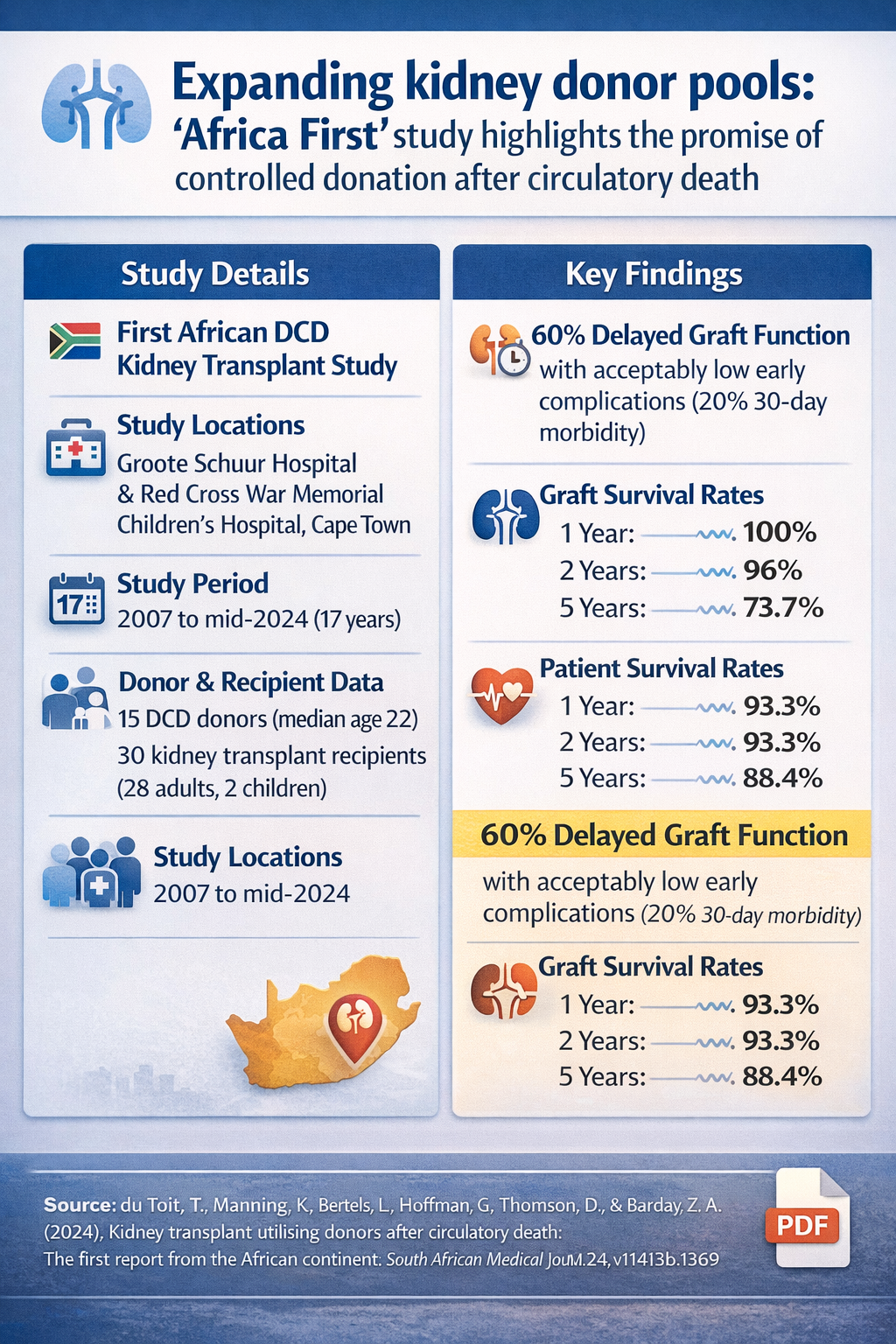

Controlled donation after circulatory death (DCD) offers a promising solution to address the growing kidney transplant demand in South Africa, with long-term outcomes comparable to international standards, despite the challenges involved.

Quick Facts

- Study: First African report on controlled donation after circulatory death (DCD) kidney transplantation

- Setting: Groote Schuur Hospital & Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, Cape Town

- Period: 2007–mid-2024

- Donors: 15 young donors (median age 22); no extended-criteria donors; no organ discard

- Recipients: 30 kidney transplants (28 adults, 2 children)

- Key early outcome: 60% delayed graft function, with acceptable short-term morbidity (20%)

- Long-term outcomes:

- Graft survival: 100% (1 year), 96% (2 years), 73.7% (5 years)

- Patient survival: 93.3% (1–2 years), 88.4% (5 years)

- Why it matters: DCD offers a viable way to expand South Africa's kidney donor pool with outcomes comparable to international data

Top

The Medical Education Network recently spoke with the research team from Groote Schuur Hospital about their groundbreaking work in controlled donation after circulatory death (DCD) transplantation in Africa.

Study Context

In South Africa, approximately 3,500 patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) are on the waiting list, but the country has one of the lowest deceased organ donor rates in the world (1.6 donors per million population). Despite the implementation of living-donor kidney transplant programs, the demand for organs continues to outpace the supply. Expanding the deceased donor pool and improving organ utilisation are essential strategies to address this gap.

One approach which is utilised with success internationally is the use of controlled donation after circulatory death (DCD), as compared to donors obtained after brain death (DBDs).

While early data from countries like the UK and USA indicated higher rates of primary non-function (PNF) and delayed graft function (DGF) for DCD kidney transplants compared to brain-dead donors (DBDs), long-term outcomes have been found to be comparable. Indeed, DCD transplants have been shown to offer significant survival benefits over continued dialysis.

Despite the success shown internationally, South Africa has not widely adopted DCD kidney transplant programs.

Editor's Note

The expanded criteria donor (ECD) is any donor over the age of 60, or a donor over the age of 50 who meets two of the following criteria: a history of high blood pressure, a creatinine (blood test that shows kidney function) greater than or equal to 1.5, or death resulting from a stroke.

Study Objective

This observational cohort study - the first from the African continent - aimed to assess the feasibility and outcomes of DCD in a low- to middle-income setting with declining deceased organ donation rates.

Study Methods

The data reviewed was obtained from prospectively maintained donor referral and kidney transplant registries of controlled DCD kidney transplants performed at Groote Schuur Hospital and Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, over 17 years from 2007 to mid-2024.

Primary endpoints were 1-, 2- and 5-year graft and transplant survival.

Secondary endpoints included the incidence of delayed graft function (DGF), 30-day morbidity, length of stay, and donor and recipient clinical characteristics.

Study Findings

Donors

Of the 229 patients referred as potential organ donors during the study period, 155 cases resulted from trauma-related incidents. Following clinical evaluation, 80 patients were identified as suitable candidates for donation after circulatory death (DCD), and families consented to donation in 21 of these cases. The donor population was notably young, with a median age of 22 years, and none met the extended criteria donor (ECD) classification. Ultimately, kidney procurement was successfully performed in 15 donors—14 adults and one child—with no organs requiring discard.

Recipients

Thirty patients received kidney transplants from these DCD donors, with organs experiencing a median cold ischemic time of 11.5 hours. Recipients were allocated based on negative complement-dependent cytotoxicity T- and B-cell crossmatch testing. The recipient cohort comprised 28 adults and 2 children, many of whom presented complex immunological challenges including multiple human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches or previous transplant history.

Post-transplant kidney function varied significantly: 12 recipients experienced immediate graft function, while 18 developed delayed graft function (DGF) requiring at least one haemodialysis session. Within the first 30 days post-transplant, 15 allograft biopsies were performed to assess graft pathology. These biopsies revealed acute tubular necrosis in 10 patients, while the remaining cases showed acute cellular rejection, borderline rejection, ascending pyelonephritis, and calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) toxicity—one patient each. Only one biopsy demonstrated a completely normal allograft kidney.

Clinical Outcomes

The median hospital stay was 16 days overall, extending to 19 days for patients experiencing DGF. Early morbidity at 30 days affected 20% of recipients, with complications including surgical site infection, sepsis, and graft pyelonephritis—one case of each.

During the first year post-transplant, three patients experienced acute cellular rejection episodes, all of which responded favourably to steroid therapy.

Long-term outcomes were encouraging: graft survival rates remained at 100% at one year, declined slightly to 96% at two years, and reached 73.7% at five years. Patient survival followed a similar trajectory at 93.3%, 93.3%, and 88.4% at the respective time points. Seven patients were lost during follow-up: three succumbed to sepsis, one died in a motor vehicle accident, and three were not reaccepted for haemodialysis following allograft failure.

Clinical Interpretation

This study demonstrates that donation after circulatory death (DCD) kidney transplantation can achieve excellent outcomes even in the context of high delayed graft function rates.

The 60% incidence of DGF (18 of 30 recipients) is substantial but not unexpected given the median cold ischemic time of 11.5 hours and the inherent physiological challenges of DCD organs. Importantly, DGF did not compromise long-term graft survival, which remained at 100% at one year—a result comparable to or exceeding many donation after brain death (DBD) programs.

The predominantly young donor pool (median age 22 years) and the absence of extended-criteria donors likely contributed to the robust long-term outcomes, with graft survival of 73.7% at five years despite the complexity of the recipient cohort.

The finding that acute tubular necrosis was the predominant early biopsy finding (10 of 15 biopsies) supports appropriate patient selection and immunosuppression protocols, as acute rejection remained uncommon and responsive to standard steroid therapy.

The 20% thirty-day morbidity rate and median hospital stay of 16 days (19 days for DGF patients) reflect acceptable perioperative outcomes, particularly considering many recipients had multiple HLA mismatches or previous transplant exposure. The absence of organ discard underscores careful donor selection and efficient logistics.

Patient survival rates exceeding 88% at five years demonstrate that DCD kidney transplantation provides durable, life-sustaining therapy for end-stage renal disease patients.

Why This is Relevant for South African Practitioners

These findings hold particular significance for South Africa's transplant landscape, where organ shortage remains a critical challenge and trauma-related deaths are disproportionately high. With 155 of 229 potential donors (68%) coming from trauma incidents, this study highlights an underutilised resource that could substantially expand the national donor pool. South Africa's high burden of road traffic accidents and interpersonal violence—tragic though they are—represents an opportunity to save lives through DCD programs where families consent to donation.

The successful implementation of DCD kidney transplantation demonstrated here provides a roadmap for other South African centres seeking to establish or expand their programs. The excellent outcomes achieved despite resource constraints typical of many public sector facilities suggest that DCD transplantation is both feasible and sustainable in the South African context. The median cold ischemic time of 11.5 hours indicates that organs can be successfully shared across geographic distances, potentially enabling regional organ sharing networks that could benefit patients in provinces without established transplant programs.

For South African nephrologists and transplant teams, this data provides reassurance that DGF—while common in DCD transplantation—should not deter program development, as it does not compromise long-term graft survival when appropriately managed. The low rejection rates suggest that standard immunosuppression protocols are effective, an important consideration in resource-limited settings where access to novel immunosuppressive agents may be restricted.

From a healthcare policy perspective, these results support investment in DCD infrastructure, training, and public education around organ donation. Expanding DCD programs could meaningfully reduce transplant waiting lists, decrease the societal burden of chronic dialysis, and improve the quality of life for South African patients with end-stage renal disease. The young donor age profile also aligns with South Africa's trauma demographics, suggesting sustainable donor availability if consent rates can be improved through culturally sensitive donation counselling and public awareness campaigns.

Original Study

References

Disclaimer:

The content in this summary is intended as an overview only and does not replace the original research. Members should review the original study before forming clinical opinions. The Medical Education Network cannot be held liable for inaccuracies or omissions.

Fact-checking Policy:

The Medical Education Network makes every effort to review and fact-check source material. Please use the contact us form to report issues