- View Candida Auris: priority pathogen on the march Currently reading

Candida Auris: A Priority Pathogen on the March

Type of article: Article and News review

Category: Infectious Diseases

MedED Catalogue Reference: MIR001

Category Tags: Infectious Diseases| Antimicrobial Resistance | Priority Fungal Pathogens | Candida Auris

Compiler: Linda Ravenhill

Sources: JAMA, CDC, WHO, Emerging Infectious Diseases

Multi-drug-resistant bacterial strains are responsible for 1,27 million deaths annually and are estimated to indirectly contribute to 4.95 million deaths. Considerable resources have been directed towards the research into, and management of, these infective pathogens.5 (pg vii)

Recently, however, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other infectious disease watchdogs have noted, with concern, the alarming global increase in cases of multi-resistant infectious fungal diseases or IFDs.

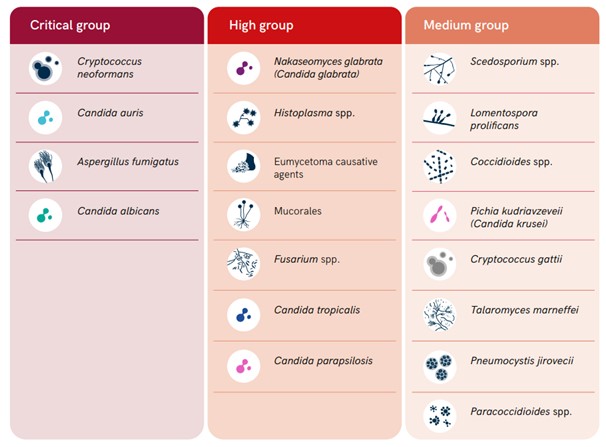

Unlike bacterial infections, IFDs have to date, received very little attention. To address this, in 2022, the WHO rereleased the first fungal priority pathogens list – the WHO FPPL. The report lists 19 fungal pathogens as priority pathogens and differentiates between those with a critical, medium and high risk. (See Figure 1)

Against this background, that alarm bells have been sounded regarding the rapid increase of Candida Auris (C.auris), an emerging fungal infective listed in the critical group in the FFPL. In the US alone, cases of C.auris have risen by almost 200% since 2019.2 While global data is scanty, it is thought that this situation is playing out in countries across the globe, including here in South Africa.

Figure 1: WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List

Note: From World Health Organisation (2022.) WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. p. 6 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241) Retrieved 23 March 2022

What we know so far

C. auris produces invasive candidiasis of the blood (candidaemia), internal organs, cardiovascular, central nervous and urinary tract systems. It also is known to cause infections of the bone and eye.5 (pg 16)

Patients most at risk are hospitalised patients - particularly those in critical care situations - and immunocompromised patients, including those with underlying severe diseases such as diabetes, TB, in particular those with previous mycosis infections, HIV patients and patients with haematologic malignancies.5 (pg 16)

Drug Resistance Profile

The pathogen is intrinsically resistant to most available antifungal medications, and some strains are pan-resistant. A 2019 paper published in JAMA indicates the pathogen is:

“…40% resistant to >= 2 drug classes 10% to all antifungal drugs 90% to fluconazole, conferring likely resistance to other azoles, 30% to amphotericin.” 1

Mortality & Morbitity

There is a high mortality rate in cases of C.auris infections, ranging from 29% to 53%.5 (pg 16)

According to the WHO:

” Patients with C. auris candidaemia had a longer length of stay in hospital or ICU than those with candidaemia caused by other Candida spp. The median length of hospital stay was 46–68 days in adult and paediatric C. auris candidaemia patients, ranging up to 70–140 days.” 5(pg16)

Furthermore, they indicate that whilst the actual rate of global infection is difficult to determine due to a lack of studies:

“An increase in the number of cases during COVID-19 pandemic has been reported by many countries. Other risk factors include renal impairment, hospital stay longer than 10–15 days, use of mechanical ventilation, central venous catheterization, total parenteral nutrition and sepsis.5(pg16)

Therapeutic Controls and Management

C. auris has a high person-to-person transferral rate, particularly within hospitals and care facilities. Its ability to form biofilms and adhere to polymeric surfaces means that normal bio-cleaning agents are frequently ineffective. The pathogen may persist on shared equipment and other surfaces if care is not taken. 4, 3(pg 2036)

This means the potential for outbreaks is high, and eradicating the pathogen is extremely difficult. The implications for hospitals, clinics and nursing homes are significant, as eradication may require shutting down wards and facilities. 5 (pg1)

What we know in South Africa

The first case of Candida Auris was identified in 2009. It was confirmed retrospectively in 2014 from a sample initially incorrectly identified as Candida haemulonii. 3 (pg 2036)

This misidentification illustrates one of the complexities regarding the control of C.auris, namely how difficult it is to identify using standard biochemical laboratory tests.3 (pg2038) The implications of these difficulties for resource-constrained environments, such as in South Africa and other developing countries, are concerning. Furthermore, it could imply that the number of cases is actually much higher than reported.

In their 2019 paper which looked into the epidemiological shifts occurring in candidemia driven by C.auris, researchers van Schalkwyk et al. reported that the pathogen was responsible for more than 10% of all reported candidemias, making it the third most commonly occurring Candida species in South Africa.4 This increase in cases denotes a clear shift in the epidemiology observed from the previous national survey conducted between 2009-2010.4

In 2018 Govender et al. (2018) published the results of their comprehensive national survey of C.auris cases, conducted over four years (October 2012–November 2016). They reviewed 1,692 cases and determined that the local C.auris clade is unique, separate from the Asian, South Asian and South American clades, indicating that it emerged independently in Africa.3 (pg 2036)

Of the cases they detected, the overwhelming majority - 93% - were found in the private sector, and 92% were located in Gauteng Province. 3, pg (2036). van Schalkwyk et al. indicated a similar distribution of cases.4 Several reasons for this demographic concentration were given, including a more mobile population rate and a higher referral rate within the province.4

The high incidence in private hospitals was attributed to the following:

-

Increased instances of critical care interventions: patients in private hospitals were more likely to receive ventilation and have CV ports and urinary catheters – prime sites of infection.4

-

Private sector patients have access to a broader range of antifungal drugs and were more likely to have already been on antimicrobial therapy before infection4

-

There are poor antimicrobial prescribing behaviours in private facilities, particularly multi-drug prescriptions and a lack of antimicrobial environments. 4

van Schalkwyk further determined that:

-

Patients with bloodstream infections had received prior systemic antimicrobial drugs at least 14 days before their diagnosis. 32% of those patients had received previous system antifungal drugs 4

-

Patients with C.auris had been hospitalised for a median length of 28 days before their onset of candidemia, in contrast with 12 days for patients with non-C.auris candidemia 4

-

Indeed hospitalisation seems to have been the main contributory factor in these patients being infected with C.auris: 31% of the patients surveyed had spent more than six weeks in hospital before their first positive culture was obtained 4

-

Patients in private sector facilities had a 3-fold increase in the odds of infection with C-auris candidemia 4

In Conclusion

C.auris is difficult to detect in a resource-constrained environment, difficult to treat due to its properties and antimicrobial resistance profile, and extremely difficult to eradicate from hospitals, clinics and care facilities once it has become endemic.

As it reshapes the candidma profile, this priority pathogen poses a significant threat.

Given the rapid rise in cases, prefaced against the ongoing battle with antimicrobial overprescribing, poor prescribing practices, and inadequate infection control practices, the question arises: will we be able to stem the march of this priority pathogen before it becomes yet another lethal endemic resident in our hospitals and communities.

Guidelines and Reports

WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action

Candida auris in newborn infants Frequently Asked Questions

References:

1. Bradley SF. What Is Known About Candida auris. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1510–1511. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.13843 Retrieved 24 March 24 Accessible on https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2749798#:~:text=Candida%20auris%20is%20a%20new,due%20to%20a%20single%20strain

2. CDC (2022). Candida Auris (2022) https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/index.html Retrieved 23 March 24

3. Govender, N. P., Magobo, R. E., Mpembe, R., Mhlanga, M., Matlapeng, P., Corcoran, C., Govind, C., Lowman, W., Senekal, M., & Thomas, J. (2018). Candida auris in South Africa, 2012-2016. Emerging infectious diseases, 24(11), 2036–2040. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2411.180368 . Retrieved 24 March 2023. Accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6200016/

4. van Schalkwyk, E., Mpembe, R. S., Thomas, J., Shuping, L., Ismail, H., Lowman, W., Karstaedt, A. S., Chibabhai, V., Wadula, J., Avenant, T., Messina, A., Govind, C. N., Moodley, K., Dawood, H., Ramjathan, P., Govender, N. P., & GERMS-SA (2019). Epidemiologic Shift in Candidemia Driven by Candida auris, South Africa, 2016-20171. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(9), 1698–1707. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2509.190040 Retrieved 24 March 2023. Accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6711229/

5. World Health Organisation (2022.) WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action Retrieved 23 March 2023. Accessible at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241

Linda Ravenhill is a medical professional with an MA in Journalism. She has worked in the medical, technology and digital development spaces for over 25 years, & has a particular interest in the impact of technology on the delivery of healthcare in the Sub-Saharan Africa region.

Disclaimer

This article is compiled from a variety of resources researched and compiled by the contributor. It is in no way presented as an original work. Every effort has been made to correctly attribute quotes and content. Where possible all information has been independently verified. The Medical Education Network bears no responsibility for any inaccuracies which may occur from the use of third-party sources. If you have any queries regarding this article contact us

Fact-checking Policy

The Medical Education Network makes every effort to review and fact-check the articles used as source material in our summaries and original material. We have strict guidelines in relation to the publications we use as our source data, favouring peer-reviewed research wherever possible. Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained here is an accurate reflection of the original material. Should you find inaccuracies, out of date content or have any additional issues with our articles, please make use of the contact us form to notify us.